This is a very WIP of a thing I’ve had in mind for quite some time. I find matrixes handy to present a spectrum of concepts and ideas (and I’m like into 3D matrixes actually but I’ll get to it in a future version maybe).

A few more notes: (as of December 2024)

- I’m using “choice” both as a synonym for an option (in a list of choices), a decision, and a list of choices. I know this is terribly messy, I’ll prolly clean this up later.

- Also I haven’t spent a lot of time defining more game-specific lingo, and narrative concepts (such as the difference between story, plot, and narrative). This is also not what I usually do but hey, I’ll also clean this later and provide a glossary in my wiki.

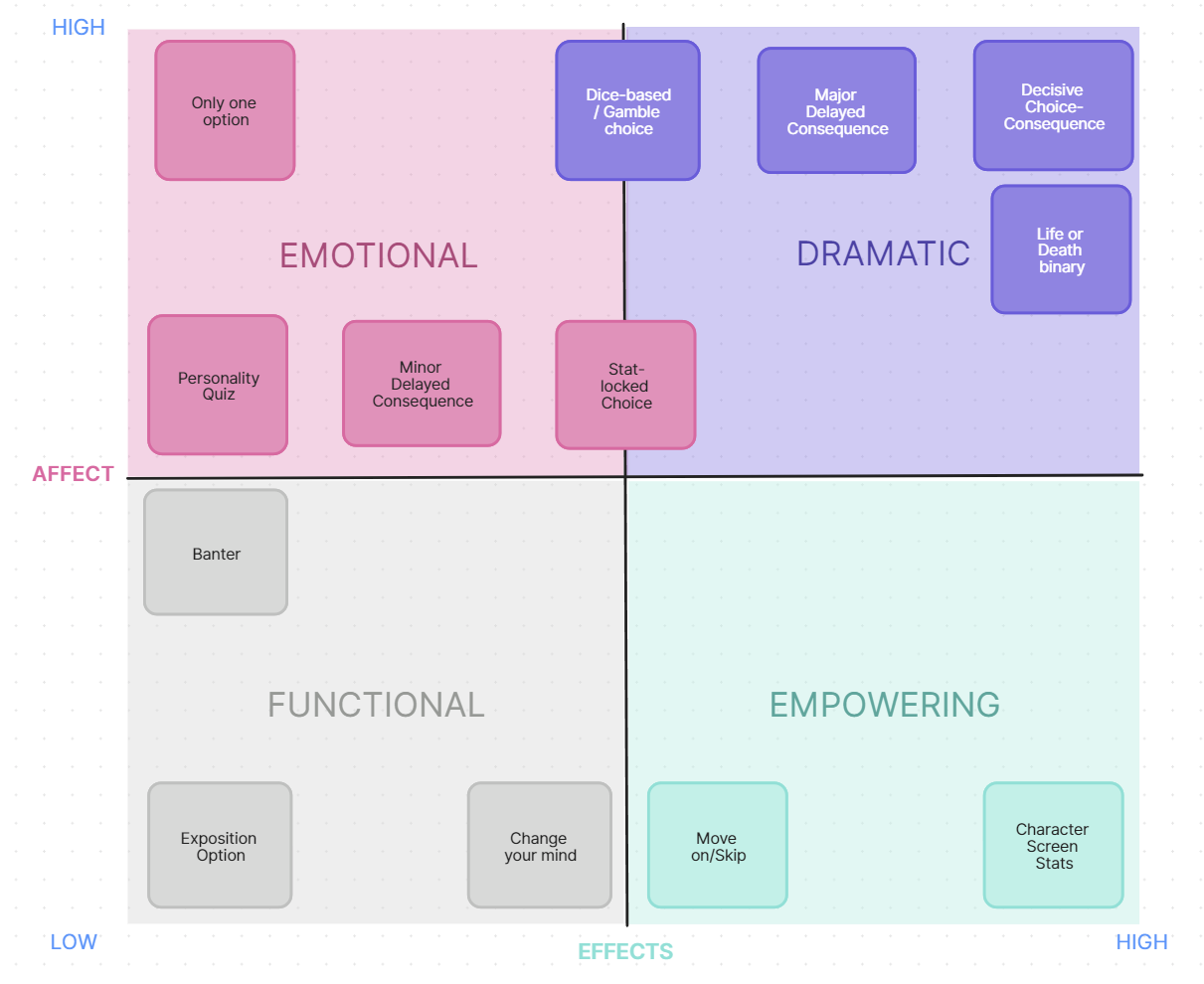

Narrative Choices Matrix

Click on any text to read more.

AFFECT

AFFECT is partly inspired by “Affect Theory” — related to emotions in human science (in broad strokes). It’s been mentioned in various readings I’ve parsed throughout the years, especially in the fields of feminist/decolonial theories. In the context of this matrix, it’s about the range of emotions a choice can express, or induce (on characters, players, the world, etc.) It is still a bit broad, but I’ll refine this if necessary later.

Low in this context is more like narrow or limited VS high is indicating a wider range of possible emotions.

EFFECTS

EFFECTS here is more about the range of concrete consequence(s) a choice can have on a story’s plot — how much it can alter events, create divergences in a plot — what we usually call “branching” in narrative design (in an arborescent type of plot).

“Low” is more about a limited potential to alter the story’s plot VS “high” as having a wider range of possible consequences.

Only one option

The “Only one option” is often presented after an emotional build-up. For example, a series of “dead-ends” is introduced to the player (false choices) as a way to build up tension and/or frustration, till there’s only one option left, and it’s often perceived as a last resort, or as a logical conclusion.

There are many endings in games that are using this. (First that comes to my mind is Persona 5 but there are many others.) You also have this in games like Like A Dragon or Judgment when interrogating a character and exhausting all options before moving further (in this case, the emotional stakes are a bit lower).

Personality Quiz

What I’m calling “Personality Quiz” is a type of choice that are about a character’s tone when saying something, but does not actually alter anything plot-wise, or how other characters will talk to them in the future. Sometimes it’s the exact same idea but phrased in different ways (from agressive to lenient); sometimes it’s a palette of reactions but the other character won’t make much note of what is said anyway. It’s used extensively in most narrative games with dialogue options that I know, from Visual Novels to Telltale games, Bioware games, Larian games etc. It was represented with emojis in Mass Effect games, notably.

The main advantage of this type of choice is to emphasize some emotional connection, and foster a personal(ized) relationship between a character and the one who plays them.

Exposition Option

The “exposition option” often starts with a “Wait…”, “Hold on…”, “Tell me more about this…” In a list of dialogue choices, it often appears at the top of a list, as a way to provide more context to the players, or remind them of what’s going on before they make any critical decision. It does not have a high impact (affect or effect-wise), but is often useful to make complex information and conversations a bit more digestible and easier to follow.

A way to make these options less artificial is often to have these options have other narrative function as well (highlighting some conflict between the characters for example). Jon Ingold (from Inkle Studios) somewhat demonstrated this during a conference, as he tried to adapt a scene from Blade Runner into an interactive dialogue.

You usually don’t want to “unlock” anything new plot-wise via these options as it could become very disorienting for the player. (Unless it’s the core mechanic or something.)

Another way to inject a bit more affect into this type of choice is to add some soft/multistep confirmation: “Are you sure you want to know more?” — suddenly it feels that there’s a danger in knowing more, which can be emotionally interesting (depending on context of course — also you don’t want to overuse this).

Dice-based / gamble choice

Choices that are solved based on a roll of a dice, or anything where the outcome is not guaranteed (and it is known to the player). It’s become more and more popular these days, with games heavily inspired by TTRPGs (Disco Elysium, Baldur’s Gate 3, Citizen Sleeper albeit a bit differently etc.) The idea is to give some sense of control/agency to the player via a calculated risk that they can consciously make and influence based on previous decisions (usually via their character’s abilities or stats). Most of the times the outcome of these choices don’t lock critical elements of a main plot, but can influence the emotional journey of a character (for example, a character can solve a same situation in multiple ways, with various losses and wins — but the situation will always be solved no matter what).

The other side of this type of choice would be the “stat-locked choice”.

Stat-locked choice

A stat-locked choice is a choice that is explicitly shown to a player only when their character meets specific conditions — usually via stats or traits. For example, in Baldur’s Gate 3, you often have dialogue options that only a character with a specific race or class or high stat can choose to say. If the character does not meet the condition, then the dialogue option won’t even show up in the list.

Some of the biggest advantages of this type of choice are about making the experience more personal(ized), based on the illusion of scarcity (not everybody will see this and I, the player, notice that the game “acknowledges” my previous decisions) and the pleasures of delayed gratification (the consequences of my choices are revealed not immediately after I chose my character’s stats and attributes) among other things.

Decisive Choice-Consequence

(might want to rename this later) This type of choice combines aspects of other choices in this matrix. It’s basically a choice that is unlocked and revealed only if the player did a series of consecutive choices before, and it usually ties to how a specific plot point unravels. It is the “reap what you sow” type of moment in an interactive story (whether good or bad).

It’s obviously the hardest type of choice to design successfully, because it’s both a choice that can lead to different outcomes (as the protagonist could also change their mind at the last minute, under the player’s control) and a delayed consequence (as it needs a build up toward it). You also don’t need a ton of them in a story usually, because a player’s attention span and memory are always limited anyway. Also, this can have a huge impact on your game’s scope, hence it’s best not to overdo them, or keep them for the most important themes/characters/plot points in your story.

Life or Death binary

I’m nicknaming this “life or death” binary, because this type of choice usually offers two options that are in opposition, with dire consequences on someone or something — a grave dilemma. It often appears as “kill that NPC or save them”, or save this person or this person instead (and you can only save one of them — which was a classic case in Telltale’s first Walking Dead game).

While this obviously can have many effects on a story’s plot (as the two consequences will be, most likely, at complete odds with each other), the emotional impact of this type of choice is, in my opinion, not as high as we might think, because it relies on some sort of a contradiction. You need to care for the parties involved if you want this choice to work; but also solving such dilemma with a simple click or button press does feel a bit… cheap. It puts the playable character in such a powerful position that it will be hard for the same character to actually care for the choices they can make (and their consequences).

Minor delayed consequence

A choice that leads to a delayed consequence can feel a bit abstract at times (both when a choice is made, and when the consequence actually happens). That’s maybe why some games relied on “This character will remember this” messaging in the past, as a way to bring more weight to some choices (artificially, at times) and feedback this more directly to the player.

It is fun to sprinkle a few nods to what was said or done before though, without having major consequences on a story’s plot. These choices are relatively “easy” to design in principle, but the bigger the game, the harder they are to keep track of, both for designers and players. (Disco Elysium does this a lot, with characters reacting to some random joke Harry might have said before, or what he’s wearing.)

Change your mind

“Change your mind” (or “Go back” or “Maybe later” or “Not now”) is a common option that is either about delaying a decision, or cancelling one entirely. It is, I think, particularly useful for multiple reasons:

– Pace the decision-making process, and potentially act as a “multistep confirmation”. Just showing that this option exists hints that something “important” might be about to happen, so the player needs to think twice before making a choice.

– Let the player review what they know before moving forward — this is also a way to pause and ponder that is a bit more embedded in the experience (rather than pressing the pause button or reloading a save).

Another less commonly used advantage of this could be about some sort of “player-induced twist” (and in this case, it would be placed higher in the matrix). Giving up something important at the last minute could be a conscious choice with potential for drama and emotion. (I guess it could almost become a “life or death binary” in that case.)

The opposite of this one is most likely the “Move on/Skip” option.

Move on/Skip

“Move on” (or “Skip”, or “Enough talking about this”) lets a character skip some secondary information (usually via dialogues) and move on to the next narrative beat. While having low affect most of the times, this type of choice can have multiple advantages:

– Pacing and structure: It can help a player parse information in a more fluid way. Having this choice often implies that there are at least two types of information (a main thread, and some optional digressions). The player’s focus is a very limited resource, and providing some sense of hierarchy in the choices can make everyone’s life easier.

– Characterization: Someone who always skips to a conclusion, or gloss over details — it can become a character’s trait. If there is a way to have other characters react to this (with a delayed consequence for example), then this type of choice could have some unexpected emotional impact in the long run.

Major delayed consequence

A major delayed consequence is a simpler version of the ‘decisive choice-consequence’, or a variant of the ‘only one option’ with heightened stakes and a build up based on previous choices. It’s basically an option with a single outcome that becomes available only after the character has made a series of smaller choices and it has many effects on the story’s plot. A rough example of this would be in Disco Elysium — if Harry makes several choices that please Kim Kitsuragi (and raise his trust’s hidden meter), then Kim will come to his rescue at a critical moment in the story. If not, this does not happen.

This overlaps with other types of choices that are being mentioned in the matrix, but I think the overall logic is this: It’s about funneling a character’s journey into one, logical outcome, after a series of smaller decisions. Rather than having a “decide X or Y”, it’s breaking down the decision into a multistep process (and often relies on meters/stats that are kept hidden to the player) with a single outcome.

Character Screen Stats

This is mostly seen in RPG-like games — related to character creation and how a player can increase/decrease stats of a character at will. While the emotional range of these interfaces is rather limited (I don’t feel lots of different things personally when adding +1 or +2 to charisma or intelligence to my character as a player), the effects of these stats can be pretty high story-wise (from locking specific interactions, to specific storylines, depending on the game).

High Affect

This will be a gross generalization, but usually anything that has a high affect has the potential to be more memorable to the player, but also more demanding emotionally wise. So it is possibly best to keep the “high affect” choices scarce (unless the experience is fairly short) to make sure they can shine properly in an interactive story.

Low stakes

Low affect/effect choices should not be discarded, because they are actually the most flexible choices to use, they also help pace an interactive story, can create contrast and surprises, are easier to understand/digest both emotionally and cognitively speaking. But if the dialogue choices only have low stakes choices, then you maybe need to make sure other parts of the game can heighten some of the affective and effective impacts of a character’s actions and decisions (via gameplay and art, for example).

High Effects

Games are often praised when they feel very reactive to a player’s actions and decisions — and story-wise, a common cliché is to think about the number of possible outcomes, branchings and endings. While these can have some value, if the emotional stakes of a journey are not heightened in other ways, then in my opinion the storytelling potential of a game will also feel limited too, or very abstract.

Having all choices making a high impact on a story’s plot is often a major risk in terms of scope (quantity can easily become the enemy of quality); these choices are also harder to keep track of and cognitively heavy, because they often need some sort of build up over time, a streamlined interface to keep track of them (hence stats and menus) and/or large consequences. It may be better to devise intricate systems that can support not too many high effect choices ultimately, just a few (or very recurring, systematic ones) that will be the most emblematic of the game’s theme/tone.

Banter(s)

Banters can be used in various places in an interactive conversation — often at the very beginning, to set the tone between characters, or during one of the secondary threads of a conversation (as a digression, or a follow up of an “exposition option”). There can be one or more options but they are more or less equivalent, and the focus is less about defining a character’s persona and tone, more about some playful dialogues to pace a conversation. Another way to see them could be a simplified version of a “personality quiz” (with a narrower range of options, if there are more than one). Usually the interlocutor has the spotlight in this case — it can be a way to show a bit more of who they are.

Laisser un commentaire